Categories

Posts in this category

- Automating Deployments: A New Year and a Plan

- Automating Deployments: Why bother?

- Automating Deployments: Simplistic Deployment with Git and Bash

- Automating Deployments: Building Debian Packages

- Automating Deployments: Debian Packaging for an Example Project

- Automating Deployments: Distributing Debian Packages with Aptly

- Automating Deployments: Installing Packages

- Automating Deployments: 3+ Environments

- Architecture of a Deployment System

- Introducing Go Continuous Delivery

- Technology for automating deployments: the agony of choice

- Automating Deployments: New Website, Community

- Continuous Delivery for Libraries?

- Managing State in a Continuous Delivery Pipeline

- Automating Deployments: Building in the Pipeline

- Automating Deployments: Version Recycling Considered Harmful

- Automating Deployments: Stage 2: Uploading

- Automating Deployments: Installation in the Pipeline

- Automating Deployments: Pipeline Templates in GoCD

- Automatically Deploying Specific Versions

- Story Time: Rollbacks Saved the Day

- Automated Deployments: Unit Testing

- Automating Deployments: Smoke Testing and Rolling Upgrades

- Automating Deployments and Configuration Management

- Ansible: A Primer

- Continuous Delivery and Security

- Continuous Delivery on your Laptop

- Moritz on Continuous Discussions (#c9d9)

- Git Flow vs. Continuous Delivery

Tue, 28 Jun 2016

Automating Deployments and Configuration Management

Permanent link

New software versions often need new configuration as well. How do you make sure that the necessary configuration arrives on a target machine at the same time (or before) the software release that introduces them?

The obvious approach is to put the configuration in version control too and deploy it alongside the software.

Taking configuration from a source repository and applying it to running machines is what configuration management software does.

Since Ansible has been used for deployment in the examples so far -- and it's a good configuration management system as well -- it is an obvious choice to use here.

Benefits of Configuration Management

When your infrastructure scales to many machines, and you don't want your time and effort to scale linearly with them, you need to automate things. Keeping configuration consistent across different machines is a requirement, and configuration management software helps you achieve that.

Furthermore, once the configuration comes from a canonical source with version control, tracking and rolling back configuration changes becomes trivial. If there is an outage, you don't need to ask all potentially relevant colleagues whether they changed anything -- your version control system can easily tell you. And if you suspect that a recent change caused the outage, reverting it to see if the revert works is a matter of seconds or minutes.

Once configuration and deployment are automated, building new environments, for example for penetration testing, becomes a much more manageable task.

Capabilities of a Configuration Management System

Typical tasks and capabilities of configuration management software include things like connecting to the remote host, copying files to the host (and often adjusting parameters and filling out templates in the process), ensuring that operating system packages are installed or absent, creating users and groups, controlling services, and even executing arbitrary commands on the remote host.

With Ansible, the connection to the remote host is provided by the core, and

the actual steps to be executed are provided by modules. For example the

apt_repository module can be used to manage repository configuration (i.e.

files in /etc/apt/sources.list.d/), the apt module installs, upgrades,

downgrades or removes packages, and the template module typically generates

configuration files from variables that the user defined, and from facts that

Ansible itself gathered.

There are also higher-level Ansible modules available, for example for managing Docker images, or load balancers from the Amazon cloud.

A complete introduction to Ansible is out of scope here, but I can recommend the online documentation, as well as the excellent book Ansible: Up and Running by Lorin Hochstein.

To get a feeling for what you can do with Ansible, see the ansible-examples git repository.

Assuming that you will find your way around configuration management with Ansible through other resources, I want to talk about how you can integrate it into the deployment pipeline instead.

Integrating Configuration Management with Continuous Delivery

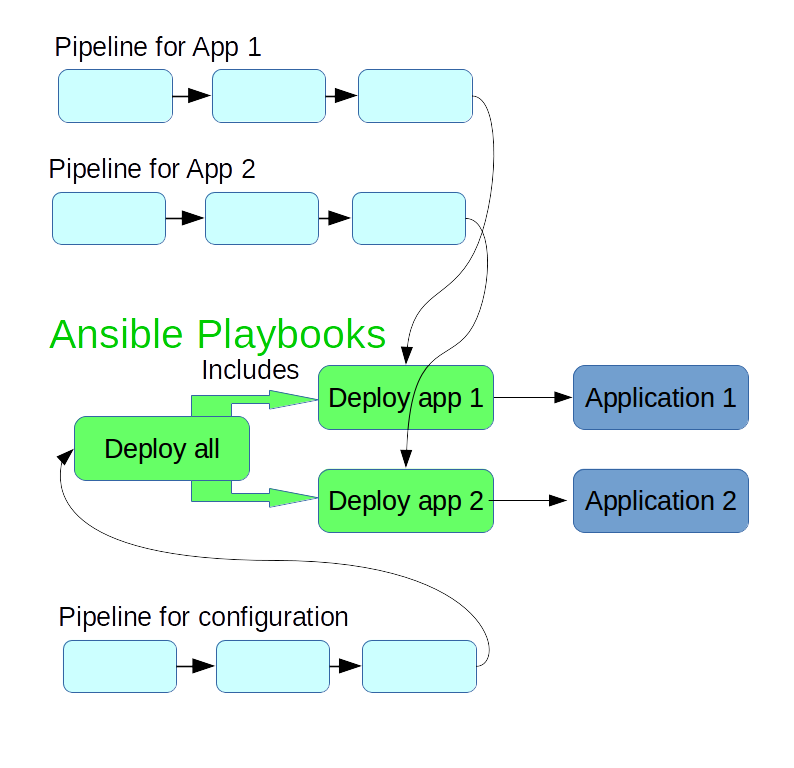

The previous approach of writing one deployment playbook for each application can serve as a starting point for configuration management. You can simply add more tasks to the playbook, for example for creating the configuration files that the application needs. Then each deployment automatically ensures the correct configuration.

Since most modules in Ansible are idempotent, that is, repeated execution doesn't change the state of the system after the first time, adding additional tasks to the deployment playbook only becomes problematic when performance suffers. If that happens, you could start to extract some slow steps out into a separate playbook that doesn't run on each deployment.

If you provision and configure a new machine, you typically don't want

to manually trigger the deploy step of each application, but rather have a

single command that deploys and configures all of the relevant applications

for that machine. So it makes sense to also have a playbook for deploying all

relevant applications. This can be as simple as a list of include statements

that pull in the individual application's playbooks.

You can add another pipeline that applies this "global" configuration to the testing environment, and after manual approval, in the production environment as well.

Stampedes and Synchronization

In the scenario outlined above, the configuration for all related applications lives in the same git repository, and is used a material in the build and deployment pipelines for all these applications.

A new commit in the configuration repository then triggers a rebuild of all the applications. For a small number of applications, that's usually not a problem, but if you have a dozen or a few dozen applications, this starts to suck up resources unnecessarily, and also means no build workers are available for some time to build changes triggered by actual code changes.

To avoid these build stampedes, a pragmatic approach is to use ignore filters in the git materials. Ignore filters are typically used to avoid rebuilds when only documentation changes, but can also be used to prevent any changes in a repository to trigger a rebuild.

If, in the <materials> section of your GoCD pipeline, you replace

<git url="https://github.com/moritz/deployment-utils.git" dest="deployment-utils" materialName="deployment-utils" />

With

<git url="https://github.com/moritz/deployment-utils.git" dest="deployment-utils" materialName="deployment-utils">

<filter>

<ignore pattern="**/*" />

<ignore pattern="*" />

</filter>

</git>

then a newly pushed commit to the deployment-utils repo won't trigger this

pipeline. A new build, triggered either manually or from a new commit in the

application's git repository, still picks up the newest version of the

deployment-utils repository.

In the pipeline that deploys all of the configuration, you wouldn't add such a filter.

Now if you change some playbooks, the pipeline for the global configuration runs and rolls out these changes, and you promote the newest version to production. When you then deploy one of your applications to production, and the build happened before the changes to the playbook, it actually uses an older version of the playbook.

This sounds like a very unfortunate constellation, but it turns out not to be so bad. The combination of playbook version and application version worked in testing, so it should work in production as well.

To avoid using an older playbook, you can trigger a rebuild of the application, which automatically uses the newest playbook version.

Finally, in practice it is a good idea to bring most changes to production pretty quickly anyway. If you don't do that, you lose overview of what changed, which leads to growing uncertainty about whether a production release is safe. If you follow this ideal of going quickly to production, the version mismatches between the configuration and application pipelines should never become big enough to worry about.

Conclusion

The deployment playbooks that you write for your applications can be extended to do full configuration management for these applications. You can create a "global" Ansible playbook that includes those deployment playbooks, and possibly other configuration, such as basic configuration of the system.

I'm writing a book on automating deployments. If this topic interests you, please sign up for the Automating Deployments newsletter. It will keep you informed about automating and continuous deployments. It also helps me to gauge interest in this project, and your feedback can shape the course it takes.